The AIR report on Delaware’s school funding system should be given to the state by the end of December.

Two dozen leaders from state and national educational organizations on Monday got a sneak peek of potential recommendations on how Delaware should fund schools.

A report by the American Institutes for Research, being paid for by the Delaware Department of Education and designed to help guide state recommendations on changing the way schools are funded is expected to be released by the end of 2023.

Representatives of Rodel, DelawareCAN, ACLU Delaware, First State Educate, the Education Trust, the Wilmington Center for Education Equity and Policy, Christina School District and a few other groups asked questions and shared ideas on the state’s funding mechanism.

That funding mechanism was established in the 1940s and did not take into account special needs students, English language learners and income disparities.

Margie López Waite, chief executive officer of Las Américas ASPIRA Academy shared stats from a 2023 study conducted by Franklin & Marshall College’s Center for Opinion Research which indicate that the First State is far from first when it comes to educational equity.

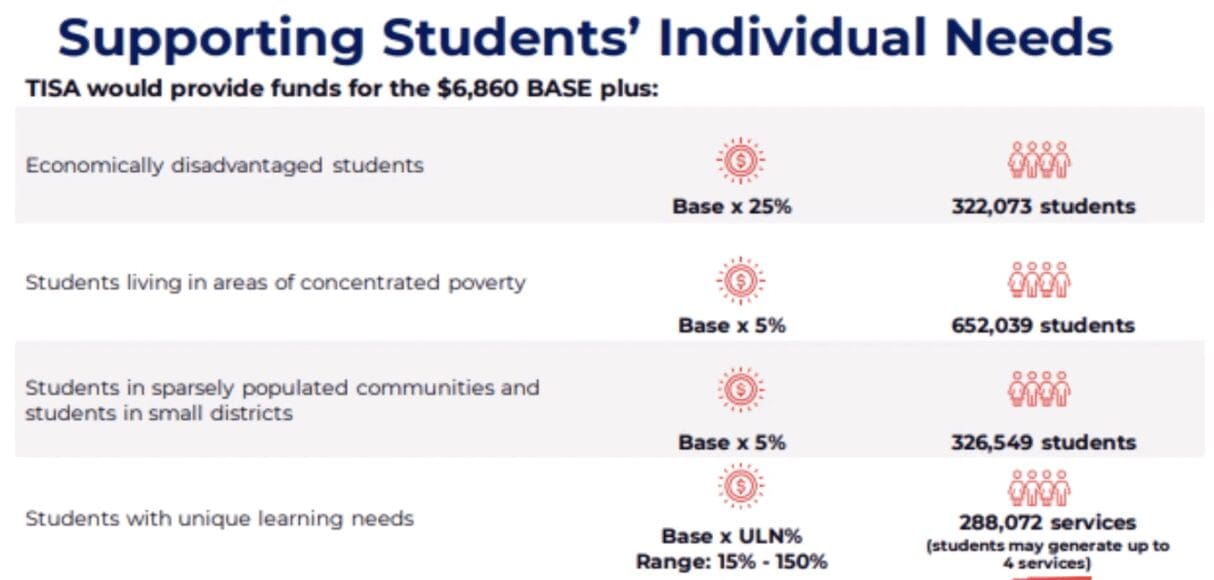

“Opportunity funding represents a small percentage of our funding,” she said. “It’s only about an additional 3% to 9% per student, while other states fund these student populations at an average of 25% to 50%, and in some states it’s up to 100% more funding.”

Opportunity funding is additional money from the state for low-income students and multi-language learners. A 2021 lawsuit settlement led to making that weighted funding permanent in Delaware.

By fiscal year 2025, opportunity funding will more than double to $60 million a year from $25 million a year.

The lawsuit was largely driven by concerns that the state’s 80-year-old school funding formula did not adequately support poor and special needs programs.

Opportunity funding is used to aid both academic and social well-being. Examples include mental health support, reading assistance, after school programs and more.

RELATED: Here’s why state wants advice on school funding

López Waite also said Monday that 64% of Delawarens do not think that the state spends enough on education, even though about $1.5 billion dollars of the state budget goes towards education.

“And when states invest more and increase funding, especially for high needs students,” she said, “it leads to positive effects on everything from educational attainment to long term earnings, so bottom-line, the message has been that money matters in education.”

Michael Griffith, senior researcher and policy analyst at the Learning Policy Institute talked about about how Delaware falls into the national landscape of education funding.

The state tends to rank in the top 25% to 30% in state per pupil expenses, he said.

“It’s deceptive, he said, because Delaware’s costs are higher than in other areas and when those expenditures are adjusted for that, “it doesn’t look as generous in Delaware.”

According to the Delaware State Report Card, the First State spends about $18,500 per student. While this is on the upper end of all 50 states, it is less than surrounding Pennsylvania and New Jersey, and is about the same as Maryland.

“Within your region three or four of the states outspend you,” Griffith said. “You’re talking about $600 per kid in Delaware. Generally it would be $1,500 per kid for English language learners or for at-risk students.”

Delaware is paying the American Institutes about $700,000 to analyze the current funding policy and make recommendations for improvements, with a focus on equity for all students.

RELATED: State to get advice on improving school funding in fall

Although the state expected the report in the fall, speakers Monday confirmed that it still should be submitted sometime in December this year.

Griffith said that many states have more categories of students with special needs. Some states have special education students categorized by mild, moderate and severe, with the funding weighted heavier towards those on the severe end of the spectrum.

He pointed out that states are now getting more specific to make sure funding is dispersed in a proper way.

Texas, he said, has more than a dozen groups.

The recommendations could include honing in on a needs-based funding system, rather than a resource-based approach.

He said decades ago when the current formula was implemented, virtually all students attended their neighborhood school, but with school choice, dual enrollment programs, vo-tech programs and all the schooling options, it’s important to establish a strictly needs-based funding formula.

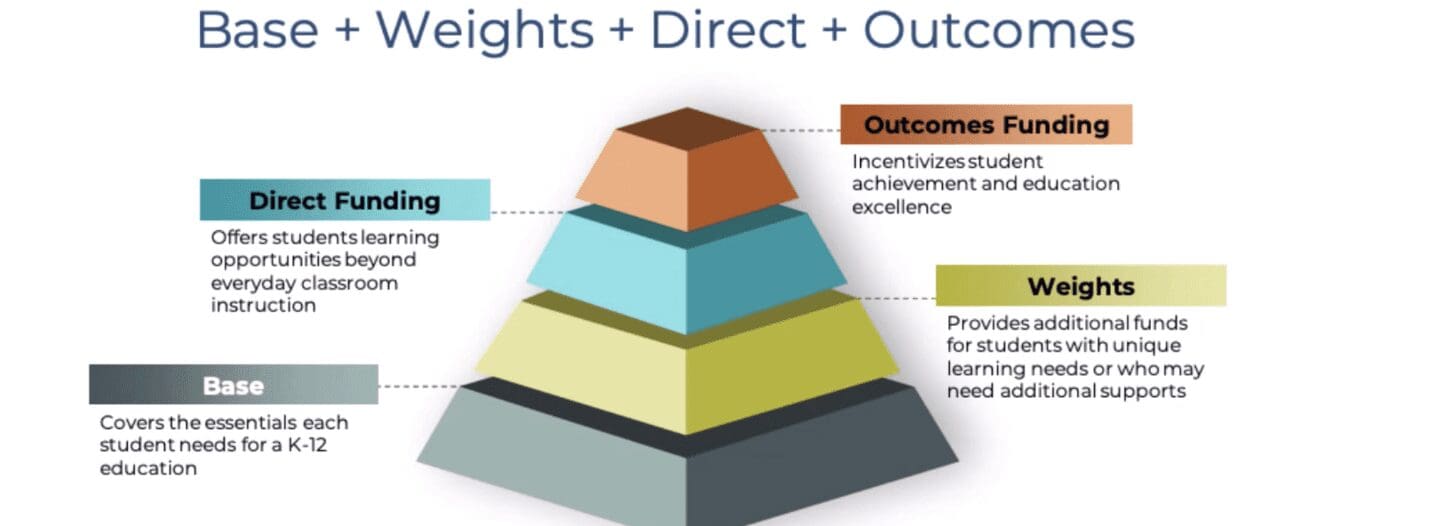

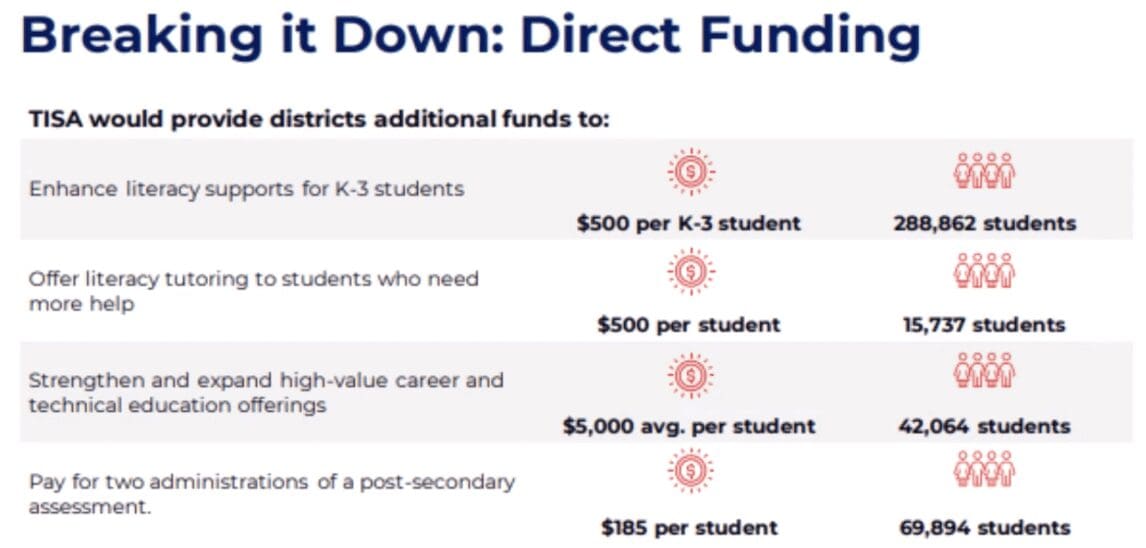

Breanna Sommers, a senior policy analyst at The Education Trust – Tennessee, explained shared visuals of how Tennessee has revamped its funding methods through the Tennessee Investment in Student Achievement Act, which became law in 2022 and replaced a three-decade-old existing system.

Tennessee has a base of $6,860, and then adds the appropriate funding based on these weights:

Districts in Tennessee then receive additional funds for certain initiatives like literacy support and tutoring.

“We lifted up all of the reports around how Tennessee was doing on different rankings, whether it was education, law centers, making the grade level and all these different things to really try to shame and embarrass, frankly, Tennessee leaders to say something has to be done because we’re not doing a good job for our students,” said Gini Pupo-Walker, Executive Director of the Education Trust – Tennessee.

She said local autonomy and flexibility are two keys to successfully reshaping a state’s education funding mechanism.

Raised in Doylestown, Pennsylvania, Jarek earned a B.A. in journalism and a B.A. in political science from Temple University in 2021. After running CNN’s Michael Smerconish’s YouTube channel, Jarek became a reporter for the Bucks County Herald before joining Delaware LIVE News.

Share this Post