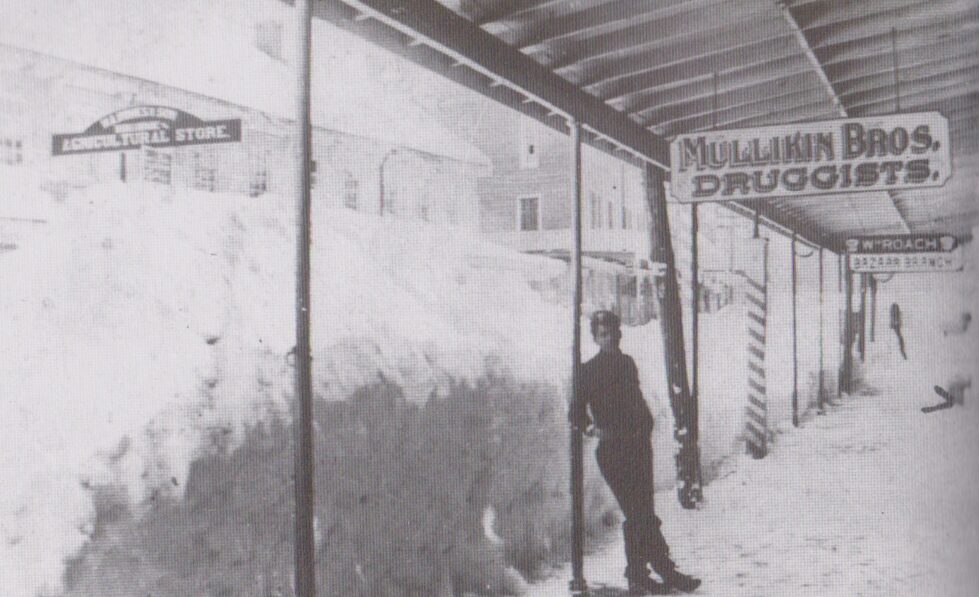

An unknown Milfordian stands on Walnut Street with giant drifts behind him after the Blizzard of 1888 (Photo courtesy of Milford Museum)

Although there have been no significant snowfalls in Milford this year, with the 135th anniversary of one of the worst snowstorms in Delaware history coming up on March 11, it is important to remember the Blizzard of 1888. The storm began innocently enough on a mild and pleasant March day, but by Sunday afternoon, the weather took a drastic turn.

“On Sunday, the wind blew from the southeast and rain began to fall in the afternoon, continuing until about 11:20 PM when the wind jumped to the northwest and at once blew a hurricane,” a statement from “A History of Milford,” compiled by the Milford Historical Society, said. “Houses rocked and trembled, trees were blown down, roofs taken off and everything loose was swept before the wind. In about an hour, the rain changed to a fine snow and the mercury sank rapidly, going down to 10 degrees by morning.”

The account continues, explaining that snow stopped by daylight and the sun appeared, but the wind blew at about 65 miles an hour, filling the air with snow as “fine as flour.”

“In places it drifted into high banks and filled every crevice,” the account, which was taken from a local newspaper, continued. “It blew again on Tuesday as fierce as the day before and the snow again fell from the northwest. Railroad and highways were blocked and stopped. Small buildings and fences were blown down and the tin roof was stripped from Marshall’s Mills. The train from Lewes got stuck and it did not reach here until Tuesday and for three days, two engines were used to pull two cars, and none came on time.”

According to the National Weather Service, snow totals reached as high as 40 to 50 inches across parts of New England. Over 400 people died in the storm. Most of them lost their lives as the economy was struggling, requiring many to try to get to work despite the weather conditions. In addition, more than 200 ships were destroyed along the East Coast.

The view of snow drifts from the second floor of the National Hotel (Photo courtesy of Milford Museum)

Weather notifications were in their infancy in 1888 and this caught many people unprepared for the storm. Another factor that led people to ignore warnings was that it was 50 degrees during the day on March 11. The rain was heavy when it began, but many simply did not think snow was possible after having such warm weather earlier in the day. Once the rain began, there was localized flooding, and the temperature began to drop quickly. As it did, the rain on the ground froze so that when the snow began, described as “large flakes, falling close together” it began to stick quickly.

The Eastern seaboard was paralyzed by the storm. Telegraph communications were cut off and ships were running aground. In Lewes, 23 vessels were reported to have run aground and there were reports that 18 sailors were frozen to death in the rigging of the boats. In Milford, a tunnel was dug to allow passage across Walnut Street to various businesses and photos taken from the National Hotel show drifts above first floor windows.

A plaque created by the Delaware Public Archives and placed at Lewes Harbor calls the storm “The Great White Hurricane.” It describes “salt spray that froze into a glassy coating the instant water touched decks, spars or rigging.”

The storm finally ended on March 14 and shovel brigades hired by railroads to clear tracks and get supplies where they needed to be. In some areas, since the most common transportation was horse and buggy, travel was stopped until a spring thaw melted the snow several days after the storm ended.

RELATED STORIES:

Share this Post